Saudi Women Drive

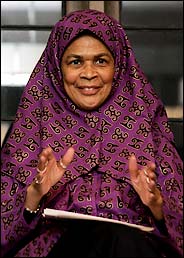

Amina Wadud

Posted Nov 8, 2013 •Permalink • Printer-Friendly VersionSaudi Women Drive

by Amina Wadud

So what’s the big deal in that? Thanks for asking.

I have been actively spreading the word, giving support and showing my enthusiasm for the Saudi women’s initiative to be permitted to drive their own cars. I celebrate with them the success of this latest initiate on October 26th which was without government backlash. About 60 women took to the wheel. None were arrested, detained, fired from their jobs, harassed in the streets, or banished from their communities. We call that progress.

But to some this may seem trite. Given a list of the top priorities for reform how does women driving get so high on the list? There are limits to this effort. First of all, only those who can afford cars are directly involved. This makes it class specific. Despite the over whelming wealth of Saudi Arabia and its comfortable GDP, there are poor people. I actually tried to photograph as many women who roll huge carts of sellable goods during the pilgrimage to share how they maneuver in temperature above 100/35 degree, covered from head to toe (literally!) in black, selling their goods, some sitting on the ground, to eat lunch, converse with one other, and bargain hard over the prices of these Chinese trinkets and synthetic clothing.

So as to issues of poverty and women’s access to resources, is this even relevant? Likewise, since no woman can get a driver’s license in Saudi Arabia, these women drivers have acquired driver’s licenses in some other countries so doesn’t that mean they are influenced by foreign cultures?

Let me step back and look at this from within a larger context of the global Muslim women’s movement.

In 2009 a global movement for reform of Muslim family law, against unequal policies and archaic cultural practices and attitudes was launched in Malaysia (http://www.musawah.org). 250 people attended, mostly women, all active for the cause of Muslim women’s equality in their own countries, of which about 50 were represented. There were many differences between the participants, but some things united us. All had experienced assault against our human dignity because we were women being blamed on our religion, Islam. Meanwhile all still held that Islam was both sacred and essential to our identity.

Even now, almost 5 years later, I cannot express how profound that moment was for me. I have been part of this global evolution/revolution for gender justice in Islam for four decades, including having worked with many of those same women present at the launching. I had argued that patriarchal interpretations were but one possible interpretation of the sacred text and provided clear and concise evidence that the Qur’an could be read BEYOND patriarchy. This egalitarian reading of the major text underlying the Islamic worldview—the fundamental source in the development and establishment of the OLDEST legal system still practiced today: Islamic family law—is also an enduring source of inspiration for more than a billion people worldwide—half of them female. Challenging the patriarchal root of interpretation and cultural practices helped herald in the current iteration of the Muslim women’s movement. It reminds us of one resounding idea: it was not Allah/God who oppresses women or demands asymmetry. It is the political will and cultural force of patriarchal interpretation.

To be sure, many of my ideas were not new. However, the circumstances under which they were presented during this current Muslim women’s movement brings greater public attention and are thus harnessed as a weapon in reform movements worldwide. Furthermore, they provide concrete evidence that efforts for gender equality are not just colonial imperialism seducing good Muslim women away from their “true” religion, culture and identity. Suddenly, greater awareness of the possibilities of freedom and justice as equality is on the table and there will be no turning back.

To be sure, the Muslim women’s movement at this time is unlike at any other time. Many of the rights granted to women at the founding of Islam: like right to life, right to private property, right to choose a husband, right to divorce, right to inherit, right to act as a witness in court—along with the most important, ontological right, the right to have an unmediated relationship with the Divine Creator—were revolutionary fourteen centuries ago. However, women were the beneficiary of these rights with little or no effort on their part. It was a gift that came with the revelation and the prophethood (The Qur’an says, “We have not sent him (the Prophet Muhammad) except as a mercy for all of the worlds”).

The Saudi women’s drive initiative demonstrates a crucial aspect of the Musawah movement: Today’s movement is the result of a critical mass of Muslim women demanding justice FOR themselves, articulating the form of that justice, and advocating the terms of it. Women decide for themselves what justice and equality will look like. They have the right, responsibility and agency to determine how they wish for that justice to be manifest and the terms of its implementation in their own contexts.

In Saudi Arabia, women-driving is a symbol reflecting the intersecting of a number of aspects of the inequality in the name of culture and religion. Although women are (supposedly) prohibited from going out of their homes without male guardianship (i.e. relatives), male drivers are almost all immigrant laborers, who are thus reduced to a status of non-persons. Otherwise, how else are they allowed to accompany the women alone? (Just like men selling female lingerie, which was prohibited recently.) Certainly there are also implications about competence and freedom of mobility.

In all these, women must choose how their own culture determines their identity, affirms their faith and defines their character. Maybe we cannot support this symbolic act until we throw off the veils of our own western bias. I am excited when Saudi women drivers are on the move because although it was only 60 women, I remember it was only one Rosa Park who ignited the American Civil Rights movement. These women herald in the inevitable change in all aspects in the lives of Saudi women.

So, I say, “You drive girl!”

Source: Feminism and Religion. Amina Wadud is Professor Emerita of Islamic Studies, now traveling the world over seeking answers to the questions that move many of us through our lives. Author of Qur’an and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective and Inside the Gender Jihad, she will blog on her life journey and anything that moves her about Islam, gender and justice, especially as these intersect with the rest of the universe.

• Permalink